“Herodotus of Halicarnassus here displays his inquiry, so that human achievements may not become forgotten in time, and great and marvellous deeds — some displayed by Greeks, some by barbarians — may not be without their glory; and especially to show why the two peoples fought with each other.”

“Herodotus of Halicarnassus here displays his inquiry, so that human achievements may not become forgotten in time, and great and marvellous deeds — some displayed by Greeks, some by barbarians — may not be without their glory; and especially to show why the two peoples fought with each other.”

~Herodotus, The Histories, translated by Aubrey de Sélincourt, revised by John Marincola.

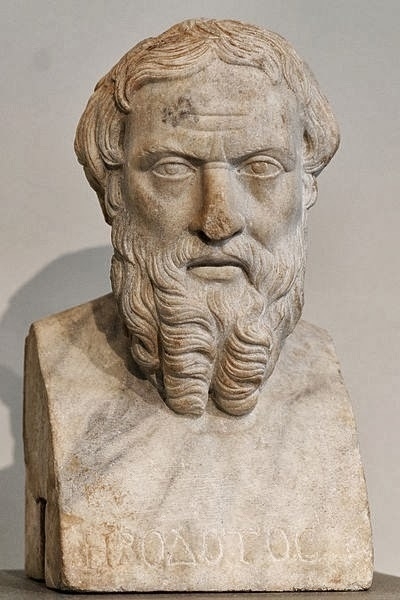

Herodotus (c. 484–425 BC) was born at Halicarnassus, which is on the Aegean coast of modern day Turkey. Cicero called him the Father of History because he is the first person we know of who systematically inquired into events of the past and tried to make sure that they had actually happened before creating his own narrative.

That seems obvious to us, but compare his book’s opening lines with the usual way of telling of memorable deeds of the past:

Sing, O Goddess, the anger of Achilles son of Peleus, that brought countless ills upon the Achaeans. (The Illiad. tr. Butler)and:

Speak to me, Muse, of the adventurous man who wandered long after he sacked the sacred citadel of Troy. (The Odyssey, tr. Palmer)Homer appeals to the goddess for inspiration, and then tells how the gods' actions led to the events following.

But Herodotus begins by saying that he’s going to tell about great things people have done and then gives a lengthy account of the Persians' version of what caused the war: Io was kidnapped by a group of Phoenecian sailors and then in retaliation Europa was kidnapped by a group of Greeks followed by the abduction of Medea which inspired Paris to kidnap Helen. Evidently the Persians thought all this kidnapping was no big deal, but “the Greeks, merely on account of a girl from Sparta, raised a big army, invaded Asia and destroyed the empire of Priam.”

All of this caused the eternal enmity between the Greeks and the Persians. No mention at all of gods, but simply the actions of men — things that can be verified by inquiry. Just for fun, here’s the original Greek text:

Ἡροδότου Ἁλικαρνησσέος ἱστορίης ἀπόδεξις ἥδε, ὡς μήτε τὰ γενόμενα ἐξ ἀνθρώπων τῷ χρόνῳ ἐξίτηλα γένηται, μήτε ἔργα μεγάλα τε καὶ θωμαστά, τὰ μὲν Ἕλλησι τὰ δὲ βαρβάροισι ἀποδεχθέντα, ἀκλεᾶ γένηται, τά τε ἄλλα καὶ δι᾽ ἣν αἰτίην ἐπολέμησαν ἀλλήλοισι.Oh, and the “word” from Herodotus? The third word in Greek is ἱστορίης, which means inquiry. It is pronounced something like istoria, and gives us our word history.

[Source: Sacred Texts]

And there you have the history of History.

~~ ~~ ~*~

This post was originally published 1 October 2013 on my old blog when I was taking an online course in Greek history. My youngest daughter, who is studying the Greek language now, informs me that the little mark above the first i in ἱστορίης is a “rough breathing mark” so there is supposed to be an /h/ sound at the beginning of the word, and the sigma at the end should be pronounced. Historias it is, then!

.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20British%20Library.jpg)