I had planned to take a class on Chaucer at my local college in the spring of 2023 but that didn’t work out for a number of reasons. To soothe my disappointment spent the time reading some of his poetry as well as various things about Chaucer and his poetry. One day I was listening to a lecture by Seth Lerer and he mentioned something I’ve never heard before about medieval reading habits. He said that people used to pick up a book they were about to read with the left hand, then open the back cover with the right hand and read the last few lines there. Then they’d flip to the front of the book and start reading from the beginning.

In an age when a large part of story-telling was retelling older stories, no one worried about spoilers. Homer and Virgil both begin their epics by telling the reader how the story is going to end.

Knowing this habit, medieval authors were fairly deliberate about the final lines of their stories, which makes for some interesting features. The last lines of The Canterbury Tales are this inscription:

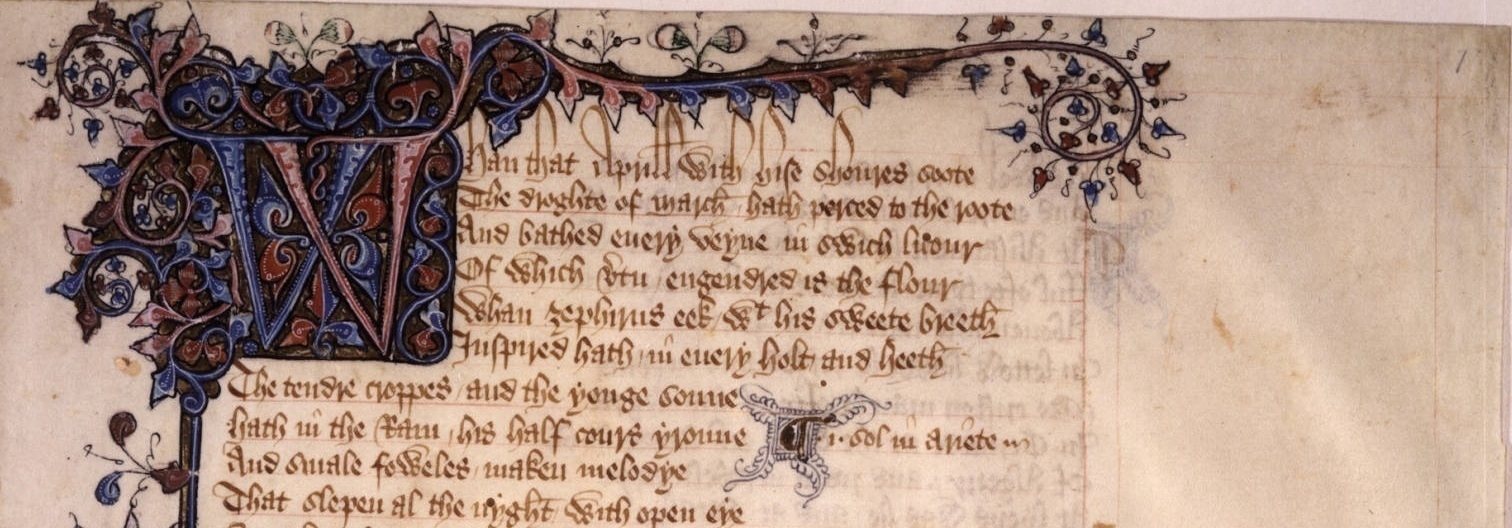

The reader would then flip to the front and begin reading the Prologue.

Curious, I flipped through some of my older books to remind myself how they ended. Most of them let you know what kind of story you’ll be reading, whether it has a happy or sad ending. A few allude to the beginning of the story.

One that caught my attention was the ending of Ludovico Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso:

And lifting his victorious hand on hie, In that Turks face he stabd his dagger twise Up to the hilts, and quickly made him die, And rid himselfe of trouble in a trice: Downe to the lake, where damned ghosts do lie, Sunke his disdainfull soule, now cold as Ise, Blaspheming as it went, and cursing lowd, That was on earth so loftie and so proud. (tr. Sir John Harington)

This is almost exactly the way The Aeneid ends:

In the same breath, blazing with wrath he plants his iron sword hilt-deep in his enemy’s heart. Turnus’ limbs went limp in the chill of death. His life breath fled with a groan of outrage down to the shades below. (tr. Robert Fagles)

Which brings me back to my earlier point about there being no spoilers in ancient and medieval literature.

And even if a reader didn’t look at the end before beginning, each book of Orlando Furioso opens with an “Argument,” a few lines that tell the reader what will happen in that book. Each canto of Spenser’s Faerie Queene also begins this way.

[I originally wrote this post last winter and don’t remember why I only saved it as a draft and didn’t publish is. Life has been crazy this year!]

.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20British%20Library.jpg)